Image source 12 Facts about slavery in Jamaica the education system refuses to teach in schools(Atlanta Black Star 17 October 2014, accessed 13 April 2023)

Thia story of the Robertsons in Jamaica starts three brothers - James, Peter and Duncan - the sons of Robert Robertson (possibly born 1718) and Janet Guild/Goold (possibly born 1720).

The brothers (and their children) who had a connection to Jamaica were three (in bold) of six children:

The English had captured Jamaica from the Spanish in 1655, and imported many slaves from Africa to work on sugar, coffee, cotton and indigo plantations. According to many reports, most of the black slaves 'lived short and often brutal lives with no rights, being the property of a small-planter class'. Many slaves ran away to join the Maroons (former Spanish slaves). A large slave rebellion known as Tacky's War broke out in 1760 but was defeated by the British.

By the early 1800s, black people/slaves were said to outnumber white people in Jamaica by 20 to 1. The British abolished the slave trade in 1807 but not the institution and slaves continued to be traded.

Some of the following text is taken from the website 'Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery', accessed in April 2023, or the Atlanta Black Star article noted under the photo above, except where indicated.

Civil registration in Jamaica – the official registering of births, marriages and deaths by the state – only started in 1878, and was enforced from 1880, covering the entire population. A central office, called the Registrar General’s Department (RGD), was established in Spanish Town in 1879. Registration is carried out through a network of Local District Registrars (LDRs), responsible for their own districts and for submitting copies of their records to the RGD. Records before the period of civil registration in Jamaica – i.e. before 1878 – are not comprehensive or complete. The International Genealogical Index, or IGI, is a hotchpotch of different sources, which is one reason why some individual births or baptisms appear twice within it, and why some records are very detailed transcriptions while others are quite basic index entries. (Source: FindMyPast website)

The St Elizabeth area of south west Jamaica where most of the Robertsons lived

Duncan Robertson (born 1756, the youngest son of Robert Robertson and Janet (nee) Guild, became a medical practitioner in Scotland.

According to the account written by Duncan's son James Peter Robertson (born 1822) in the book 'Personal Adventures and Anecdotes of an Old Officer', published in 1906, Duncan Robertson '... was educated for the medical profession and settled for many years in Jamaica where he practised as a physician, and as a member of Council got the title 'Honourable', eventually becoming the owner of a very fine estate there called Friendship'.

Duncan Robertson is believed to have arrived in Jamaica by 1780. On 30 November 1787 and recorded as a 'surgeon', Duncan married the widow Ann Finlason (nee Luttman) (also of St Elizabeth). Ann was previously married to Thomas Finlason, a Jamaican planter (from 23 August 1774). It is not known (yet) if Thomas and Ann had had any children. Ann owned the 'Friendship' estate in the St Elizabeth area of Jamaica with her brother. Duncan acquired half the estate through his marriage to Ann and apparently bought out the other half from Ann's brother.

According to his son James' account, 'In his old age he (Duncan) married a second wife [sic - it was actually his bride's second marriage, which the account then confirms] who was quite a young girl, a Miss Lutman. During her husband's last illness [referring to *Miss* Lutman], my father, Dr Robertson, attended him professionally; and he made the very extraordinary request to my father that he would, after a reasonable period, marry the young widow, who had no relations living on the island [sic - he then goes on to refer to her brother, unless he wasn't actually living there]. This he did, and became owner of part of Friendship; the other half he purchased from Mr Lutman, his wife's brother; and the whole estate thus become his property'. James' account continues '... after many years of happiness, Mrs Robertson died, and some time after my father returned to Scotland ...'. See below from 1819.

Note that the name 'Luttman' appears again below - it seems Duncan's nephew, also Duncan, decided to name one of his (mixed) sons Duncan Luttman Robertson. Is it possible that Ann Henegan, Duncan junior's later partner and a mulatto, was connected with Duncan senior's estate?

The 'Red Book of Scotland' states that Duncan was appointed to the Legislative Council in Jamaica and that his Jamaican estate was located in St Elizabeth, West Jamaica. Duncan returned to Scotland in 1819 - see below. (Source: 'Red Book of Scotland' by Gordon MacGregor)

A second conflict known as the Second Maroon War broke out from 1795 to 1796.

According to James's book, Duncan Robertson (born 1856), when '... out in the Maroon War in Jamaica ... had a narrow escape of his life. He was shaving one morning in the open air, having hung up a little glass against a tree, when one of the enemy fired a poisoned arrow at him, cutting his chin open. Knowing the deadly nature of the wound, he, with his razor, cut the piece clean out on the spot, and thereby saved his life. The mark of the wound is clearly to be seen in his portrait, painted by Sr Henry Raeburn, which hangs in my dining-room.'

John Robertson (1771 - 1818) was the son of Peter Robertson and Janet (nee) Adamson), the nephew of Duncan Robertson (born 1756) and cousin of Duncan Robertson (born 1781), the son of Duncan Robertson's older brother James. John Robertson was said to have been already in Jamaica when his younger cousin Duncan (born 1781) arrived in around 1801 - see below. It is not yet known if John or his uncle Duncan arrived first (or if, as has been suggested in James Peter Robertson's book, his cousins 'were taken to Jamaica when young men by my father'.

John Robertson (born 1771) trained as a medical practitioner and became a planter in Jamaica. He owned the Belmont/Bellemont estate in the St Elizabeth area of Jamaica. He may have married a woman with the first name Anne around 1804 - see below.

Duncan Robertson (1781 - 1850) was the third son of James and Isabella Robertson. His father James had settled in Callander, Scotland. Perhaps encouraged by his namesake uncle or his cousin John Robertson (born 1771) who was also already in Jamaica (see below), Duncan is believed to have arrived in Jamaica by around 1801 ('in his early 20s' - it was said he had lived in Jamaica for 'nearly fifty years' when he died in 1850).

Duncan Robertson was an attorney and acted in that role for both his uncle's property Friendship and his cousin John's property Belmont/Bellemont - and (it is said) possibly later inherited them.

Duncan's story continues below from 1806.

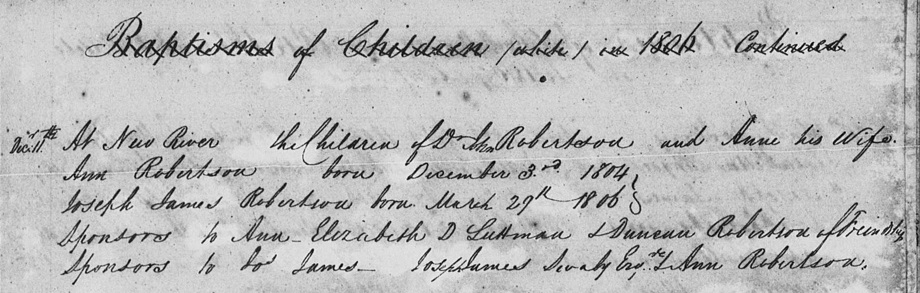

Extract from the 'Baptisms of White Children in 1806', showing two children born at New River to John Robertson and 'Anne his wife'

Intriguingly, a John Robertson and 'Anne his wife' had two children born at New River in 1804 and 1806, both of whom were not baptised until 1806:

Various family history records suggest that John Robertson married Caroline Swaby in 1804, which raises the obvious question of who was 'Anne his wife' in the above record? Was 'Anne' (a) a mistake in the register, (b) another woman, or (c) a previous wife, before Caroline? Is it possible that Anne died after the birth of Joseph James Robertson in 1806 and as a result he ended up marrying Caroline Swaby in 1806, so the children all thought of Caroline as their mother and Anne was forgotten?

Also, in the baptism record above we see that Ann's sponsors were Elizabeth D Luttman and Duncan Robertson of Friendship, while Joseph James' sponsors were Joseph James Swaby and Ann Robertson (likely the wife of Duncan Robertson, nee Luttman). Elizabeth Luttman may have been the sister or niece of Ann Robertson nee Luttman, Duncan Robertson's wife. Joseph James Swaby was John Robertson's father-in-law; he owned the estate known as New River, also in St Elizabeth.

John and Caroline Robertson (nee Swaby) had the following children. Based on the baptism of their children Janet and Mary in Scotland, it would appear that they travelled to Scotland around 1809 and again by 1817 (a year before John died).

Note for reference (as these terms are used in the registers):

Duncan Robertson junior had several children with Ann Henegan, described in the registers as a 'free mulatto' and later a 'free person of colour'.

Who was Ann Henegan?

It is not clear who Ann Henegan was. She may be somehow connected with (or be the daughter of) Matthew Henegan, likely a white man, and an unknown African woman.

According to 'Jax B' on a rootschat thread, Ann Henegan gave birth to a son in 1800 with a David Morrice.

From 1806 to 1826 - children born to Duncan Robertson and Ann Henegan

Baptism of Caroline Robertson in 1806 (Source: FindMyPast)

The register of 'baptism of children and adults, not white, in 1806' records the baptism of a Caroline Robertson, born in July 1805, the 'reputed daughter of Dr Duncan Robertson junr by Ann Henegan'. Two lines down in the register, Ann Henegan is also recorded as being baptised on the same day. She is described as 'about 25 years of age, a free mulatto'.

The 1813 baptism register notes in the 'persons not white' section the following additional 'reputed children' of Dr Duncan Robertson (junior) and Ann Henegan:

The 1819 baptism register records two more children to Duncan and Ann Henegan, described as 'a free person of colour'.

Interestingly, directly under the baptism record of Isabella and Jane is Ann Robertson, a mulatto slave baptised on the same day, without any parents listed. Could this be a relative?

According to the same rootschat discussion noted above, (a) Ann Henegan was in possession of three female slaves in 1817; the slave return is signed with a cross and countersigned by Dr Robertson; (b) Duncan Robertson had another child with Ann Henegan - Elizabeth Robertson, baptised on 20 August 1826 in St Elizabeth, Cornwall, Jamaica.

John Robertson (born 1771) acquired Bellemont in 1811. At this time there were 123 'enslaved people'. John was recorded as the owner until his death on 21 September 1818.

In 1811, Duncan Robertson was recorded in the Jamaica Almanac at Eden Mount, owning 32 slaves and 12 stock. He was again listed in the Almanac in 1812, 1818, 1821, 1825, and again in 1830 at Gilnock owning 81 slaves and 184 stock.

Ann (nee Luttman) Robertson, the wife of John and Duncan Robertson's uncle, Duncan Robertson, died at Friendship in July 1813 and was buried there on 20 July 1813.

After Ann's death, Duncan Robertson (born 1781) inherited or took over the 'Friendship' estate. His then 63 year old uncle Duncan Robertson returned to Scotland where he acquired property that he renamed Carronvale. He married Susan Anne Jane Stewart on 15 November 1817 at Dull, Perthshire, Scotland. Susan was the daughter of Captain (later Colonel) Robert Stewart, junior, of Fincastle. Duncan and Susan had three children:

John Robertson (born 1771), the son of Peter and Janet Robertson (nee Adamson), died on 21 September 1818 at Newington, Edinburgh. At the itme of his death he was noted as residing at Gartincaber in the country of Perth. For reference, there is a 'John Robertson Burial Ground' in Greyfriars graveyard in Edinburgh where his father Peter Robertson is interred.

The Morning Post of 29 September 1818 described John Robertson as 'of Bellemont, St Elizabeth, Jamaica, many years a medical practitioner on that island'.

The following is the text of John Robertson's will, made on 16 May 1818:CC8/8/149 John Robertson of Bellemont in the parish of St Elizabeth, Jamaica. Residing at Garlincaber in the county of Perth. Executors: John Chambers of Northampton Estate, St Elizabeth; William Aldam of Warminster Estate, St Elizabeth; Duncan Robertson of Friendship Estate, Jamaica (at present in Great Britain); Joseph Lawes Swaby of Montpelier (at present in Great Britain); James Robertson, writer, 2 Heriot Row, Edinburgh (cousin); and Caroline Robertson (wife).

Inventory

£1000 sterling in deposit by the British Linen Company, £75000 sterling in deposit receipt by Sir William Forbes and Company, £167 12s 3d balance of account current with the branch of the Bank of Scotland at Stirling. A debt due from Major E. M.Pherson of the 79th regiment.

Will

Executors to be trustees for whole property.

Payment of just debts, sickbed and funeral expenses. £200 per year to wife Caroline Robertson. Should she wish to live again in Jamaica she shall be able to occupy my house in Bellemont and use all household furniture within it. £500 to her in order to purchase furniture which shall remain her absolute property.

My mother Janet Robertson to be allowed possession rent-free throughout her lifetime the second flat at number 10 Buccleuch Street, Edinburgh, which belonged to my father and which has been occupied by her since his death.

My father sold to Sir John McLean, Lieut. Col. of the 27th regiment of foot, the lease of the farms of Gaskenloan and Dalwhinnie in Inverness-shire which he had obtained from the Commissioners of the Forfeited Estates. £90 per annum still due from Sir John McLean for the remainder of this lease, which I allow my mother to draw for the rest of her life. If she survives after the end of the lease then my trustees to pay her £50 per annum for the rest of her life.

The residue of the whole proceeds, rents and profits of my estate real and personal estate to be spent by my trustees to pay towards the clothing, maintenance and education of my beloved children Ann, Joseph James, John, Janet, Peter, Eliza, Caroline and Mary Margaret Adlam and any other children which I may leave at the time of my death until they reach the age of 21 or at marriage. The surplus each year to be invested in stock in the three percent consols as an accumulating fund to be added to the capital. My estate to be shared between my children equally as tenants in common and not as joint tenants.

Should my children all die before age 21 then my property to be divided one third to my wife, one third to my sister Jessy Mitchell [possibly his older sister Janet], wife of William Mitchell of Gorden Hall, North Britain, the final third to my brother Archibald Robertson of Dunsinane at present in the parish of St Elizabeth, Jamaica.

Executors and trustees to also be guardians of my children.

Codicil adds £100 annuity to wife Caroline Robertson in addition to that already allocated and £1000 to buy a suitable house for her.

Source of the above information: John Robertson of Bellemont', Legacies of British Slavery database (accessed 2 April 2023)

In 1823, Belmont/Bellemont estate, formerly owned by John Robertson, was recorded as being in the possession of John's cousin Duncan Robertson (of Gilnock Hall). The property remained 'registered to John Robertson (deceased) as late as 1839.

The 68 year old Duncan Robertson (born 1756) died in Edinburgh on 12 February 1824. He was buried at Larbert churchyard.

On the death of their father, Duncan Stewart Robertson (aged 5) inherited Carronvale whilst the 2 year old James Peter Robertson inherited another estate, 'Roehill', located in Perthshire.

In 1829, Duncan Robertson (born 1781) was recorded as the joint owner of 'Struan Castle' along with Alexander Robertson. Alexander is believed to be Alexander Robertson, the son of James and Isabell Robertson (nee Grahame) (born 1 September 1783, baptised 5 September 1783, Callander (BDM Record) - 1854, Callander (BDM Record)), recorded as an absentee owner when awarded compensation of £657 5s 10d first for 40 slaves, then a received further compensation for 54 slaves on the Struan Castle estate. In Pigot's 1837 National Commercial Directory Alexander Robertson was recorded at East Mains, Callander; in 1851 Alexander Robertson aged 64 [sic] was living at 32 East Mains Callander with his brother James (born 1790) and was described as 'proprietor in Jamaica'. Alexander inherited £1000 under the will of his brother Henry Robertson of Mansfield Callander, proved 21/10/1854.

A three-month old 'quadroon' named Duncan Daniel Rose was baptised in Cashew, in the Parish of Saint Elizabeth, in the County or Cornwall, Jamaica on 28 March 1830 to Ann Robertson. The father was named as Daniel Rose, and both parents were recorded as 'unmarried'.

For the child to be a quadroon, one of the parents would need to be white and the other mulatto.

It has not been possible yet to definitively connect Ann Robertson with other members of the Robertson families living in Jamaica at the time but it is assumed she was full white.

It is believed that Daniel Rose may have been born around 1806, was living in Hanover (Jamaica) in 1817, and died on 1 April 1882 in Williams Field, Saint James, Jamaica. There have been suggestions that Daniel's father may have been a man named James Whitehorse Rose from Scotland, and his mother an African slave, but there is no documentary evidence to confirm this.

Daniel Rose and Ann Robertson may have had at least one more child, a girl named Isabella Rose, born in 1833 in Manchester, Jamaica.

For more information on the Rose family, see this page.

Samuel Sharpe led the largest uprising by enslaved people in 1831. It started out peacefully, with enslaved Africans refusing to work. But things escalated and, in resistance, Africans burnt down houses and warehouses full of sugar cane, causing over 1 million pounds worth of damage. More than 200 plantations in north Jamaica were taken over as more than 20,000 enslaved people seized control of large chunks of land. Many plantations were destroyed. The 'plantocracy class' (which included Duncan Robertson (born 1781) - see below) carried out 'ferocious reprisals'.

Continued racial discrimation and marginalisation of the black majority led to the Morant Bay rebellion in 1865 which was put down by the Governor 'with such brutality that he was recalled from his position'. (Source: Wikipedia article on Jamaica)

Duncan married Bridget Daly sometime before 1831. Bridget was the daughter of a prominent attorney James Daly of Black River. Unfortunately for Duncan, Bridget died at Friendship (which Duncan's uncle appears to have left by 1819) on 23 October 1831 aged 19. (Note that this was around the time of the slave uprising).

After the death of Bridget, Duncan then married Elizabeth Frances Smith, the daughter of Edward Smith. They had the following children, including one born in Scotland:

During his time in Jamaica, Duncan Robertson owned or managed four plantations - Gilnock Hall, Belmont, Friendship and New Buildings. It is understood that he purchased the last plantation outright. He was also attorney for seven other estates by 1832 'including those of the Fosters and Foster Brhams at Elim and Mesopotamia, and that of John Chambers and Northampton.

Duncan Robertson was also actively involved with the militia in Jamaica. He was the 'Custos' of St Elizabeth and Colonel of the St Elizabeth Regiment of Foot Militia. He was said to have been 'heavily involved' in defeating the Slave Rebellion of 1831-2 and for this was presented with a ceremonial sword now held by the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto Canada. Sometime later he was a Major General of the Jamaica Militia.

After 1834, Duncan remained at Gilnock Hall. In 1838 he was noted in the Jamaica Almanac as having 70 apprentices.

The fear of more uprisings as well as other factors prompted the British to abolish slavery in Jamaica on 1 August 1834. At that time, the British attempted to make all enslaved Blacks remain working for the same masters as apprentices. The system was a failure, and that also was abolished. Enslaved Blacks received their unrestricted freedom on 1 August 1838.

According to the Atlanta Black Star 'In order to sustain the exploitation of Blacks, an ideology of racism was developed to make the terms African, 'negro' and 'slave' interchangeable. The primary objective of this ideology was to categorize Black Africans, including those on the island, as less than human.'

According to one source:

After the abolition of slavery in Jamaica in 1834 (and the end of the Apprenticeship system in 1838), formerly enslaved people began acquiring land, though the process was difficult due to economic and social barriers imposed by the colonial government and former plantation owners. Many freed Jamaicans pooled their resources to purchase abandoned plantations or smaller plots of land, leading to the rise of free villages and peasant farming communities in the 1840s and 1850s. However, large-scale plantation ownership by black Jamaicans was rare in the immediate post-emancipation period due to limited access to capital, high land prices, and efforts by the planter class to maintain control over agricultural production. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, some black and mixed-race Jamaicans who had accumulated wealth through trade, farming, or professional work were able to purchase plantations. However, widespread black ownership of large estates remained limited due to the economic dominance of white and foreign landowners.

As a result of the British government abolition of slavery, slave owners were paid compensation based on claims received. Duncan Robertson of Gilnock Hall and his uncle Peter Robertson of Scotland submitted a claim for £3517 2s 7d relating to the 'Friendship' estate, with 184 enslaved individuals.

James Peter Robertson claimed in his book that a William Morris, a former West India merchant, was keen to return to Jamaica 'to look after his own interests', and decided to take Robertson with him. Robertson noted in his book that the slaves were well-treated before the slave trade ended and were actually doing quite well after empancipation, but the 'proprietors' (despite being paid 'compensation') were actually in a worse situation because the former slaves no longer wanted to work. Eventually, he said, 'the owners of the land were actually startving and in many instances were forced to abandon their estates.

According to his book, James Peter Robertson 'stayed the greater part of my time in Jamaica with my cousin, the Honourable Duncan Robertson of Gilnock Hall'. It is worth noting that there was an age gap of 41 years between the two cousins.

James Robertson's book states that his cousin's '... so-called slaves had taken their emancipation, but things went on exactly in the same manner as previously: house-servants, coachmen, grooms and the whole establishment, continued on precisely the same footing.' He added that 'I moved about the island a great deal'. He narrated the following story:

Having gone with a young friend to travel on business, we arrived at a sugar estate near Savanna-le-Mar, some two miles from the town, on the second night out. There we found an old gentleman in charge, who was bigger in his complaint that his splendid fields of sugar-cane were rotting in the ground and being devourced by th negroes' pigs, the negroes themselves refusing to do a stroke of work. There was a cartload of sugar-cane standing at the mill, and I proposed, half in fun, that we should grind it ourselves. Off we started, set the mill going, and I began to stuff the canes into the rollers. We had no sooner began than out came the negroes from their settlement, stopped the mill, and ordered us back to the house, where we did go, after some lively passages and strong words between the old gentleman and the negroes.

Robertson then noted that 'the whole village turned out, men and women, some with axes, some with cutlasses or clubs'. In response, a Mr Smith brought out a brace of pistols and another gun (for himself). After threats of being shot, the workers retreated back to their homes. After he went to bed, he stated that a 'black face, with a large knife in its mouth, appeared for an instant' in the dark but was driven off.

Robertson stated that he then went to stay at 'my own place, Friendship, and found the old housekeeper who had been there in my father's time'. He noted that 'the factor in charge of the estate was a cousin of my own, a Robertson, and he and his elder brother had been taken to Jamaica when young men by my father. The younger brother remained as factor of Friendship, married a black wife, and had a flourishing family. His brother settled at Kingston and remained a bachelor'.

Who was the cousin at Friendship who had an older brother? There would appear to be two possiblities but in both cases the older brothers are known to have married and had children. Could it be the other way - the younger brother remained a bachelor?

Or it may be another set of brothers.

According to James Peter Robertson's book, the Chief of the Robertson clan wanted to sell part of the ancestral property but '... needed to get the permission of the two next heirs (he had no family himself) to the chieftanship, and it was ascertained, by going back a good many generations that the legal heirs were my two cousins in Jamaica. With their permission (they receiving a small sum as compensation) he sold part of the estate.'

This happened again, this time for the sale of the entire estate but, before the sale went through, the Chief died and James' bachelor cousin in Kingston 'succeeded to the title and estates.' James noted 'Here was a comically sad state of things. The prospective chief of the Robertsons (his nephew) was a delightful black man' ... 'Fortunately, however, the chief married and had a family , and so the black man's nose was put out of joint.'

The 'black man' in the above line appears to refer to the son of his married cousin ('the prospective chief'), however it is not clear who is meant by 'the chief married and had a family'. Did this mean the bachelor married?

James returned to Scotland and attended Edinburgh Military Academy where he studied military drawing and surveying. Whilst at Edinburgh he received a commission and was gazetted to the 31st Regiment in 1842. See the Scotland page for further information.

Duncan Robertson died on 9 May 1850. A memorial to him in Black River church reads as follows:

The Hon. DUNCAN ROBERTSON, Member of Her Majesty's Privy Council in this island, Major General of Militia and Custos Rotulorum of this parish...having been 24 years Custos, 20 years Major General and 13 years Member of Council. As Custos, he was remarkable for firmness of purpose, decision of character and ready attention to parochial duties. As General of Militia the essential service he rendered his country in assisting to quell the rebellion of 1831 will long be remembered. As Member of the Privy Council he fearlessly and conscientiously discharged the duties of that office during a series of years when legislation was rendered peculiarly difficult and trying...d 9 May 1850, leaving a widow and five sons, aged 69 years 6 months. Erected by the inhabitants of the parish."

The property at Belmont (said to be situated about 2,000 feet above sea level, near Malvern in the Santa Cruz Mountains) remained in the Robertson family until around 1875 as a coffee plantation, later abandoned for cattle raising and pimento growing. Up until the early 1960s there was still an old marble tomb at Belmont Estate which had the inscription, "Caroline Robertson. Born 11th October, 1785. Died 7th April, 1874." - Caroline was the wife of Duncan's cousin John - see below.

Page created 4 April 2023, updated 6 March 2025 (various minor edits and corrections). Copyright Andrew Warland. (andrewwarland(at)gmail.com)