DNA sampling of Warlands from the Dorset area indicates clearly that their male (Y-) DNA derives from the people with the Y-DNA haplogroup R-L21 who arrived in Britain from around 2,500 BCE, displacing and intermixing with another group of individuals who arrived from around 4,000 BCE. Over 2,000 years passed before the arrival of the Romans and both the 'Brythonic'-speaking people who occupied what is now England ('Britons'), and the Gaelic-speaking people who occupied the area of what is now Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man, created multiple communities across the land.

It has been speculated that the Brythonic-speaking communities developed their own dialects of Brythonic over 2,000 or so years but may have been able to understand other Britons, in the same way that Gaelic-speaking communities had a similar language.

The Roman Period (54 BCE to 410 CE)

The Romans under Julius Caesar invaded Britain around 54 BCE. According to the article in Wikipedia on the Roman Conquest of Britain:

By the 40s CE, the political situation within Britain was in ferment. The Catuvellauni had displaced the Trinovantes as the most powerful kingdom in south-eastern Britain, taking over the former Trinovantian capital of Camulodunum (Colchester). The Atrebates tribe whose capital was at Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester) had friendly trade and diplomatic links with Rome and Verica was recognised by Rome as their king, but Caratacus' Catuvellauni conquered the entire kingdom some time after AD 40 and Verica was expelled from Britain.

The Romans invaded Britain from 43 CE. Vespasian set up his headquarters in the area of Lake Farm in present-day Dorset (where the Warlands lived 1700 years later), where they would have definitely been in contact with the local Britons. It is tempting to speculate that the Briton ancestors of the Warlands lived in that area at the time and were still there 1,400 to 1,500 years later.

The Romans used the generic word 'Celt' to describe the local population, giving names to each 'tribe'. In reality, there were two types of Celts: (a) 'Brythonic Celts' (located in what is now England) and (b) 'Gaelic Celts' (located in what is now Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man).

In what is now the Dorset area, the primary Brythonic population or tribal confederation were the Durotriges. To their north were the Dobunni, to the east the Atrebates and to the west were the Dumnonii. According to the website link in this paragraph:

The tribe had no discernible pre-Roman tribal centre and consisted of a number of fiercely independent baronies rather than a single unified state. However, there was a mint at Hengistbury Head which may denote some sort of central administration. Their territories were possessed of an unusual density of powerful hillforts. ... The civitas capital of the Durotriges is nowadays accepted to be the large walled town of Dorchester (Durnovaria), however, there is no epigraphic or documentary evidence to support this assumption.

According to the Romans in Britain website, '... the Durotriges resisted Roman invasion in AD 43, and the historian Suetonius records some fights between the tribe and the second legion Augusta, then commanded by Vespasian. By 70 AD, the tribe was already Romanised and securely included in the Roman province of Britannia.

The Britons survived the Roman occupation, perhaps the first sign of their hardiness.

The Anglo Saxon Period (c450 CE to 1066 CE)

Saxons began to arrive from around 450 CE after the Romans left. They appear to have initially settled in the east and south, then moved inland, pushing the Britons west and (it is said) enslaving between 10% and 30% of the population. An unknown proportion of the Britons had been Christianised by the Roman priests.

The so-called Volcanic Winter of 536 was, according to the Wikipedia link 'the most severe and protracted episode of climate cooling in the Northern Hemisphere for 2000 years. According to the link, the actual source of the volcanic eruption remains to be found - and several have been rejected. The historian Michael McCormick has suggested in this 2018 Harvard University publication (also quoted in this Science online article) that 536 CE was 'the beginning of one of the worst periods to be alive', with terrible famine in most parts of Briton and Ireland. This bitter cold returned in 540 and 547 CE. To make things worse, the Bubonic plague appeared in the early 540s. According to 'The Anglo Saxons' by Dan Snow (2021, pages 54 and 55), 'the communities of south-west Britain ... were suddenly abandoned in the mid 500s' and 'the south-west of Britain appears (from the archaelogical record) to have been hit very hard and to have remained depopulated for decades' ... 'acute shortages of food must have led to increased violence'.

According to 'The Anglo Saxons' (pages 166 to 167), the Angles and Saxons likely looked down on the local Britons. Local communities in Europe that had previously been governed by the Romans were called 'walas', meaning 'foreigner' or 'stranger' by the Germanic speaking people. The same word was used by the Anglo-Saxons to describe the Britons; by the 12th century it was used for the area known as Wales. Prior to that, however, the word 'wealas' meant any and all Britons, wherever they were located. The word can be found in names such as Walton (Walas Town) and came to be synomymous with 'slave' (walh or wealh). According to Snow, 'the hostility between (the Anglo-Saxons and the Britons) grew deeper especially between the many already-Christianised Britons and the pagan Anglo-Saxons - especially after the later converted to Christianity and regarded the Briton's version to be wrong (for example in relation to the date when Easter should be celebrated).

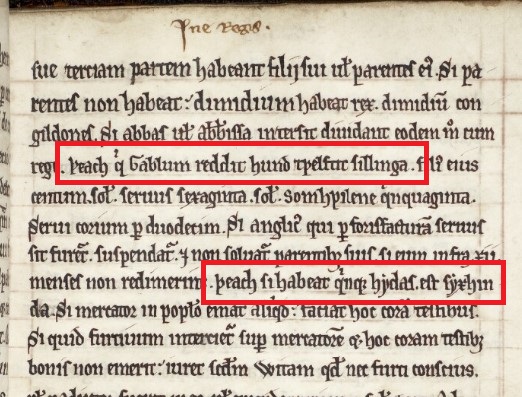

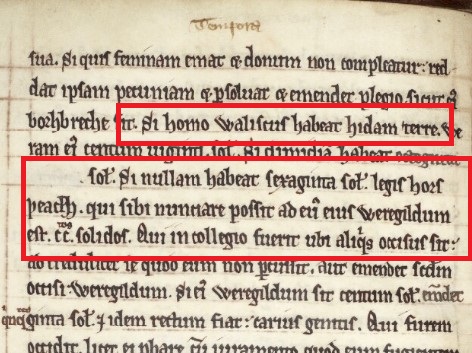

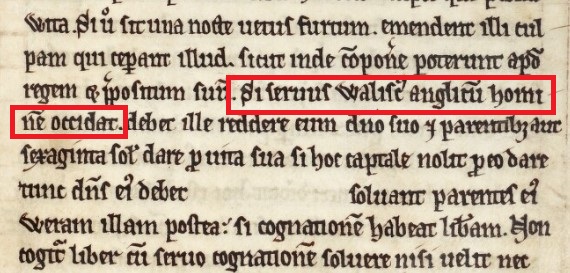

The laws of Ine, King of Wessex from around 688 to 726 AD refer to both free and enslaved Britons in Saxon society. The laws use the word 'wealh', 'wilisice' and 'waliseus' to describe the local population; these words are synonymous with 'Welsh', meaning the local population.

In the above image, the word 'wealh' is used twice (it looks like 'peach'). This word, which is related to 'Wales' and 'welsh', is the word used by the Saxons to describe the local Britons, whether as freemen or slaves. In the first example, it refers to a 'Welsh rent-payer' (said to be the highest class of Welsh peasant) while the second simply refers to a 'Welshman' who owns five hides (of land) - which is quite a lot given that one hide was considered enough for one family.

The image above has two references, the first to a 'homo waliseus' (Welshman) who has a hide of land. The second refers to 'The king's horsewealh (Welsh horsemen), who can carry his messages'. According to one researcher, this line could mean that 'an unfree hose-servant in the king's service was to be paid for as a freeman'.

The last image above states that 'If a Welsh slave kills and Englishman, then he who owns him shall surrender him to the lord and kinsmen or pay 60 shillings for his life'. (If the owner doesn't pay, then 'the avengers are to deal with him').

The laws of Ine also refers to 'Welsh ale' ('cervisie Wilisce') to be paid (among other items) as 'food rent from 10 hides'.

According to Dan Snow, 'during the eighth century the ethnic identities of the English and the Britons had sharpened, and with it the hostility between them. Offa's Dyke was an apparent attempt to isolate the Britons to the west and protect the Saxons to the east.

Late 700s - arrivals of the Vikings

But, by the late 700's, a new threat emerged - the arrival of Vikings. The extent to which the local Britons were used to help defend Anglo-Saxon lands will never be known but the meaning of the word 'warland' implies that whoever farmed that land or worked on it as a slave was required to contribute to the defence ('waru') of the land. Further research might help with understanding if it was mostly the Anglo-Saxons landholders who were required to assist with defence, or if the local Britons were also dragged along. Not everyone on the land would have been required to defend it; someone still had to carry out the regular farming industries and the Britons were likely to be the mainstay of this work - even to the point, as noted by Rosamond Faith who stated that 'the warland population was the backbone of the long-haul transport system of Anglo-Saxon England'.

We need to keep in mind here that according to DNA sampling, the Warlands of the mostly Danelaw area of Oxfordshire were not Britons but likely came with either the Anglo-Saxons or Vikings.

The ancestors of the Warlands who lived in the primary Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia managed to survive, but it will never be known if they were ever enslaved. In any case, the Saxons of Wessex and Mercia clearly regarded the local Britons ('wealhs') as having lesser-status than their own, although those who lived on 'warland' were likely to have had more freedoms and may have been very good workforce - see Dr Rosamond Faith's writing on 'warland' on this page.

Arrival of the Normans

The arrival of the Normans from 1066 likely resulted in two main outcomes from the original Britons who had survived Anglo-Saxon society. The first outcome was that they likely became 'villeins', a form of serfdom that existed until the late 1500s. Those Britons who lived and worked on what was documented as 'warland' then took on that word as a surname.

The Black Death of 1348 CE

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that, according to the most authoritative source, reached Weymouth, Dorset before the Feast of St John the Baptist on 24 June 1348. According to the Dorset History Centre website page titled 'The Arrival of the Black Death in Dorset', two ships landed at Melcombe, with sailors infected with an illness called pestilence. The first locals died on the Eve of St John the Baptist, on 23 June.

Around 40% to 60% of the population of England died as a result of the Plague. According to the Wikipedia page Black Death in England, 'the decrease in the population caused a shortage of labour, with subsequent rise in wages, resisted by the landowners, which caused deep resentment among the lower classes', leading to the so-called Peasant's Revolt of 1381. This was one of the reasons why serfdom ended in England.

The Plague returned in 1361 to 1362, killing a further 20% of the population. According to the Dorset History Centre website page link above 'the plague returned again thirteen years after its first arrival (in 1348) and fresh outbreaks every ten or twenty years meant that the population levels never recovered. Across Dorset labour intensive arable farming gave way to an increase in the number of sheep.'

What do make of this?

It is tempting to conclude that the Britons who remained on the 'warland' were regarded as good labourers and farmers because they had *always* worked that land for 3,000 or so years.

They survived the Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, then the Normans, and at least two bubonic plague outbreaks. Is it possible that the Britons who ended up on, and were named after, 'warland' took the place of those people who died from the Black Death of 1348? That is, with the death of so many people, land-owners sought replacements among the Britons (who may not have identified as such by then).

The Britons who remained in the areas govered by the Anglo-Saxons, Vikings and then Normans lost their original language; those Britons who continued to speak it (or their dialect) were pushed into Wales, Cornwall and/or left for Breton in France.

Page created 5 January 2025, updated 9 January 2025. Copyright © Andrew Warland. (andrewwarland(at)gmail.com)